Grant Woodward: Turning schools into exam factories isn't the answer

I ALWAYS thought teachers had it fairly easy. Spend breakfast browsing the lesson plan you put together over those long summer holidays, then home in time for Countdown and a bit of light marking.

But if they ever did take a stroll along Easy Street (and I’m no longer sure they did) then Michael Gove’s hyperactive four years in charge of education certainly put paid to that. And it’s not doing much for our kids, either.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTo begin with I thought Gove’s renewed emphasis on testing was a good idea. After all, if you believed the hype Joey Essex could bag half a dozen GCSEs these days they had become so easy.

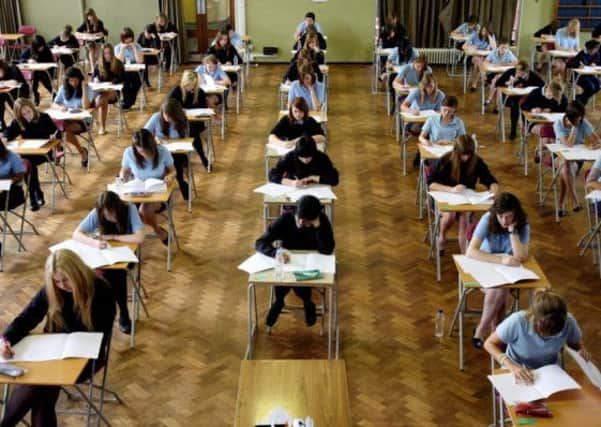

But the upshot is that his reforms are turning schools into exam factories and children into numbers rather than individuals.

And passing tests alone is no preparation for the world outside the classroom, the challenges and knock-backs it dishes up.

We need to encourage individual thinking and tenacity – the very things this strait-jacketed system seems intent on stamping out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThen there are the workloads and paperwork this new regime has brought with it. One former teacher told me she was in school for 6.30am and would be working on the laptop at home until 11pm. She quit because, in her words, “if I hadn’t I’m not sure I’d have seen 40.”

A brilliant classroom assistant we know told us she didn’t want to become a full blown teacher because of all the form filling and box ticking. It’s a loss to teaching but who can blame her?

Children need stability and consistency. That’s not going to happen if they have a succession of supply teachers because their own is riddled with stress.

Teaching is a vocational career. You’re never going to get rich doing it, but if you take away the satisfaction and joy of shaping young lives and turning out well-rounded human beings then there isn’t much incentive left.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd the dismal figures for the retention and recruitment of teachers shows that’s exactly what’s happening. Teachers are leaving the profession in record numbers while the Government has missed its target on recruitment for the last four years. Then you have schemes like Teach First, which trains new teachers on the premise they sign up for two years, then probably go and do something else. Essentially the Government is admitting it can’t keep them in teaching for the long haul and sell it as the rewarding profession it should be.

And this testing of our children has reached ridiculous levels. Baseline tests for four-year-olds risks putting kids in a pigeon hole from which they never break out. Children develop at different speeds but the system doesn’t seem to allow for that.

In Scandinavia children don’t even enter formal education until seven and yet still do better than us, which suggests this rigorous testing from the time they first stick on an oversized uniform isn’t the answer.

At the same time it encourages teachers to view pupils as grades rather than individuals, because they know that if the school’s pass rate falls below a certain level there will be hell to pay.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course we should expect schools to give our children the necessary nudges to ensure they reach their full potential.

But turning schools into places where the only thing that matters is maths and English isn’t giving them the tools they’ll need to survive and thrive in the wider world.

School should be about opening youngsters’ eyes to the possibilities in front of them. Giving them a good look at a wide range of subjects and disciplines that might encourage them to be the architects, artists or, oh, I don’t know, the ballerinas of tomorrow.

And kids aren’t daft, they can see what they mean to today’s post-Gove schools.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDiscussing an upcoming parents’ evening, my friend’s daughter wondered aloud: “Maybe this time my teacher will want to talk about me, instead of tests.”

It’s enough to make you weep.

Grubby life of football stars

WHAT a tawdry picture the Adam Johnson trial painted of your average top flight footballer.

Dumped in the dock by his former girlfriend Stacey Flounders, she told Bradford Crown Court that Johnson had admitted to a string of conquests as he told her of his dalliance with a teenager in his Range Rover.

Flounders says he didn’t tell her how many women he’d been involved with, but she suspected he was cheating when she was pregnant with their first – and apparently last – child.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn fact, while she was texting him cute pictures of their little girl, he was busy bombarding a schoolgirl he knew had just turned 15 with one of hundreds of sleazy messages.

Good on Flounders for dumping him, but you’d have thought she might have seen the light before he was arrested on child sex charges.

After all, his previous girlfriend gave him the heave ho after he reportedly bid £12,000 for a date with model Katie Price in a charity auction.

Johnson’s behaviour reeked of someone who felt a sense of entitlement. That their fame and bank balance bought them immunity from acceptable bounds of behaviour. And we know plenty more like him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNow he’s set to pay the penalty, with jail time likely after being convicted yesterday of sexual activity with a 15-year-old.

Let his story be a lesson to every young aspiring sports star. Talent’s no good if you can’t engage your brain.

Pension warning doesn’t add up

ACCORDING to a study by the Labour Party, we need to be putting 15 per cent of our earnings into a pension to make sure we’re not penniless when we retire.

That’s fine by me – just as long as my editor agrees to give me a 15 per cent pay rise, that is.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBack in the real world, if the Government keeps pushing the retirement age up at the rate it has been then none of us need to worry about life after we’ve finished work – because we’ll never get to experience it.

Maybe if successive governments hadn’t fed the insane house price inflation over the last decade or so then we’d have a little bit more to put aside for a rainy day.

Then there’s the risk that if we do plough 15 per cent of our earnings into pension pots it could disappear down the drain in the next, apparently imminent, banking crisis.

If, by some miracle, you do have some spare cash you’re probably better off sticking it under the mattress.