Leeds nostalgia: New book chronicles history of the YEP

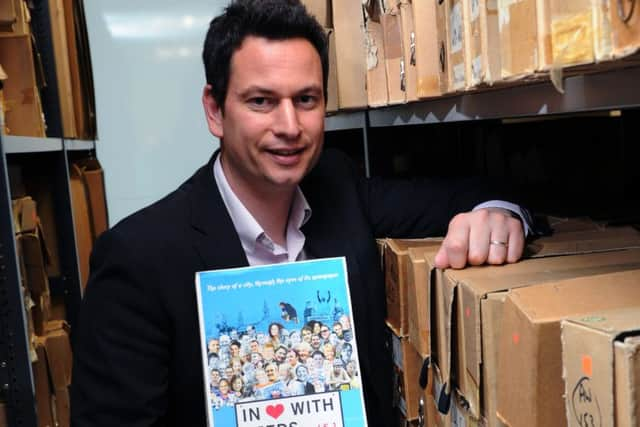

Penned by former feature writer and comment editor Grant Woodward, who recently left the business, it provides a fascinating insight into one of the city’s longest running institutions.

Did you know, for example, that the man who conceived the YEP, Charles Pebody, then editor of the Yorkshire Post, collapsed three days before its launch and never returned to work?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe very first edition of the YEP was published on September 1, 1890 and since that time it has created an invaluable record of events, chronicling all kinds of events, including royal visits, the outbreak of wars, ‘Beatlemania’, national tragedies, such as the sinking of the Titanic, the long list of luminaries who hail from the city, its industry, football club, its standing in the world and perception in the minds of its people.

Mr Woodward writes: “Throughout the course of its life, the Yorkshire Evening Post has been a witness to history. For one and a quarter centuries it has told the story of Leeds and its people, reporting on the events that have helped shape their lives and that of the city they call home.”

When the YEP came into existence, the population of Leeds stood at around 53,000, compared to today’s half a million or so. In that time, the city (and indeed the paper), has changed enormously and perhaps one of the biggest has been in transport.

Leeds was once dubbed ‘the motorway city’ but even before it was connected to the capital via the M1, it set precedents. In March 1928, the first traffic lights in the country were installed at the junction of Bond Street and Park Row. At the time, the YEP described it as: “an all electric policeman,” adding that job could not be made obsolete.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

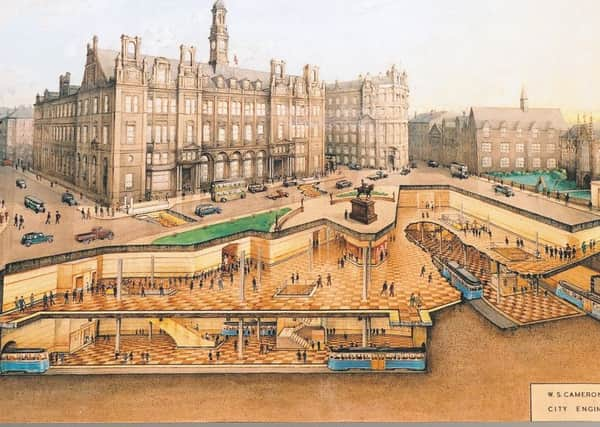

Hide AdLeeds has had many first but it has also had its fair share of missed opportunities and one such was the 1930s plan to create an underground, similar to that in London, with trains running to all parts of the city. Detailed plans were even drawn up by the council’s lead engineer, with a huge multi-level station under City Square but the project was controversial, expensive and was shelved when the Second World War broke out, after which the city had neither the will nor the cash to finance such an ambitious project, although, as the book optimistically notes: “The plans have never officially been rejected.”

Other things which made Leeds famous and which are chronicled in the book, includes the Quarry Hill flats development, the largest social living project of its kind of Europe at the time. It used the Garchey waste disposal system, which effectively meant tipping all rubbish down the kitchen sink, after which and via a series of pipes, it was transported to grinders and eventually a furnace, where it was burned to generate heat, which was used to power the laundry.

Dr Kevin Grady, recently retired director of Leeds Civic Trust, said: “Newspapers are invaluable for the historical record. If you want to know what was going and what people were thinking, you go to paper. The YEP was the notice board of the city.”

In Love With Leeds is published by Great Northern Books, £20: www.gnbooks.co.uk