Why do people volunteer to fight in foreign wars?

Guy Fawkes, George Orwell and Osama bin Laden might sound like an unlikely trio, but they are united by one striking feature – they all volunteered to fight in foreign conflicts.

Throughout history people have upped sticks and travelled abroad, putting their lives at risk to fight for a country other than their own.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s a subject that Dr Nir Arielli, Associate Professor of International History at the University of Leeds, has studied in detail and in his new book From Byron to bin Laden: A history of foreign war volunteers – he seeks to identify the common traits, and differences, that exist between people who feel compelled to get embroiled in these tumultuous events.

“If you look at the volunteers who went to Syria in the early stages of the ongoing conflict there they were motivated by images they saw on TV, and if you read the memoirs of International Brigade veterans from the Spanish Civil War they were motivated by reports they read in the newspapers. So images of suffering are very important in prompting people to go,” he says.

“In Spain you had people wanting to defend democracy and in Syria it was people fighting against a regime carrying out acts of brutality.”

He says the situation in Syria changed when the so-called Islamic State (IS) began talking about creating a Caliphate. “They tried to appeal not only to fighters but also to women and even families. This became a state-building project which wasn’t what the International Brigade was trying to do.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Arielli points out there are many different reasons why people choose to put themselves in the line of fire. “Some are drawn to a conflict because of a sense of adventure, but they can also be pushed away from where they are, be it because they’re marginalised or under surveillance or simply because they’re bored.”

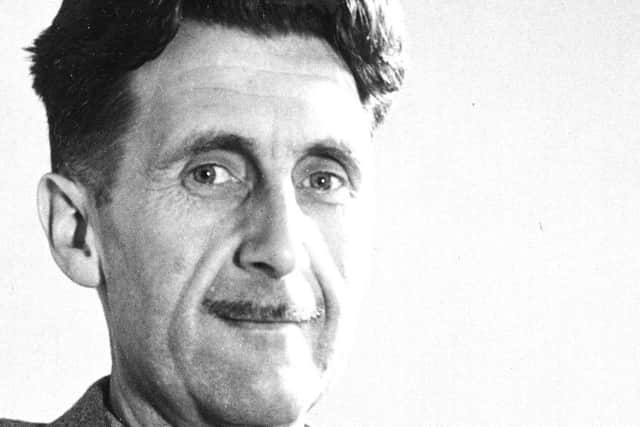

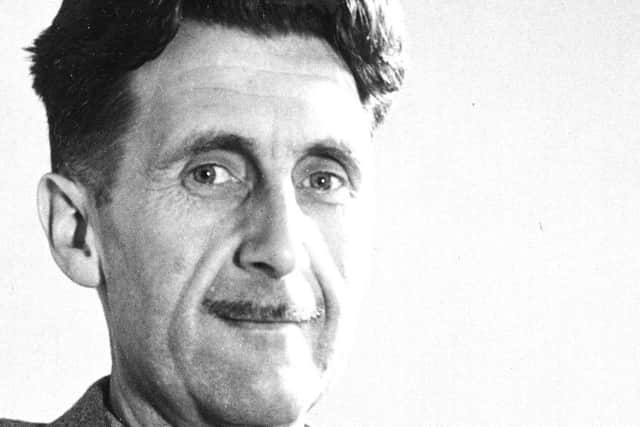

During the 1930s, the rising tide of fascism was rightly seen as a threat and the likes of Laurie Lee, WH Auden and George Orwell were among those that participated in the Spanish Civil War.

Dr Arielli says there is usually an ideological dimension involved. “For instance George Orwell was an anti-fascist and Che Guevara was a leftist revolutionary, but there are a lot of people who saw themselves as anti-fascists in the 1930s, or leftist activists during the Cold War, but not all became foreign war volunteers so there’s something different about these individuals that sets them apart.”

Those who do go abroad and fight are following a well trodden path. The Crusades, which involved the creation of a Christian army to fight in the Holy Land, date back to the 11th century, while closer to home there’s a certain Guy Fawkes who is now part of British folklore. “Guy Fawkes went over to the Low Countries and fought alongside the Spanish against the Dutch Protestants. What’s different with Guy Fawkes compared with modern day volunteers is back then there wasn’t really an expectation that a person would serve his or her country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There was no national service or conscription and armies relied largely on mercenaries, many of whom were recruited from other countries. This kind of international fighting force was very common in the 16th and 17th centuries.”

There’s another dimension to Fawkes’s story. “When he returned to England and got involved in the Gunpowder Plot he became a terrorist rather than a foreign fighter.”

These days terrorism is a depressingly familiar issue and one that is rarely out of the news. It has attracted hardline views, with the Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson saying last month that anyone who joined IS shouldn’t be allowed back in the UK.

Dr Arielli is more nuanced in his assessment. “If you look at the recent attacks in Britain they weren’t carried out by foreign fighters and one important thing to remember is that a lot of the people who volunteer to fight abroad for ideological reasons become disillusioned and come back demoralised. It’s up to the security services to assess cases on an individual basis, we can’t assume all of them will become terrorists.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe notion of going off to fight for a particular cause has global appeal and numerous recruits have come from Yorkshire down the years. “In Leeds Town Hall there’s a plaque commemorating about 20 people who went over to fight with the International Brigade and there’s also a memorial in the main square in Sheffield,” says Dr Arielli.

Among those he interviewed for his book was Steve Gaunt from Selby. “He was working in a travel agency in 1991. The fighting in Croatia was just kicking off and he followed the news intently and one day he decided to go and fight for the Croats.

“It was a spur of the moment decision and he travelled to Zagreb. The Croatians didn’t know what to do with these foreign volunteers but he was shipped off to the front and was even injured.”

Gaunt still lives in Croatia and has written about his experiences. “His book’s called War and Beer, which were the first two words he learned to say in Croatian.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile men dominate this story, there are some instances where women have become involved in conflicts. “Whichever historical events you look at, 90 per cent or more of the people who go to fight are male. But there are female volunteers. Often when they go over, whether it’s to somewhere like Spain or to Israel, their roles are restricted so they often find themselves working as nurses or drivers. But we have had a few cases of women fighting.”

People like Yorkshire-born Flora Sandes. “She initially went over as a nurse to help Serbs fighting against the Austrians but very quickly her unit retreated and she decided to take off her nurse’s uniform and join the Serbian army. She spent several years with them and was involved in heavy fighting.

“More recently we’ve had women joining Kurdish organisations in northern Syria and fighting against the Islamic State.”

So the impulse to fight for a cause hasn’t changed, it’s the causes themselves that have. “At one time the main fault line was between right and left and communism and fascism, even later during the Cold War. But in the last couple of decades religion and the clash between civilisations has come back into focus,” he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Our perception of foreign fighters still depends on the cause they’re fighting for as it always has been.” In other words most people would view someone going abroad to fight for IS differently to someone who was going to fight against them.

Dr Arielli believes volunteer fighters have something to say about who we are. “These are people who go off to do something unusual and I think they offer us a way of better understanding foreign conflicts.

“They also tell us a lot about war and what we think about bravery and it’s actually quite a telling little phenomenon that gives us an insight into what makes human beings tick.”

From Byron to bin Laden – A History of Foreign War Volunteers, published by Harvard Press, is out on January 26.

Famous names who chose to fight

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLord Byron – In this country he’s known as the bohemian poet who scandalised British high society. In Greece, though, he’s revered as a war hero. He died of pneumonia fighting Ottoman rule on April 19, 1824, and the anniversary of his death is now a day of celebration to hail Greek culture.

George Orwell – In 1936, he went to Spain to fight for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He didn’t join the International Brigade but the little-known Marxist POUM. He was shot in the throat and later wrote about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia.

Che Guevara – Once Fidel Castro’s right hand man, he wanted to spread revolution in other parts of the developing world and was killed trying to do just that in Bolivia in 1967.