Ken Loach reflects on Kes half a century on from classic Barnsley-based film

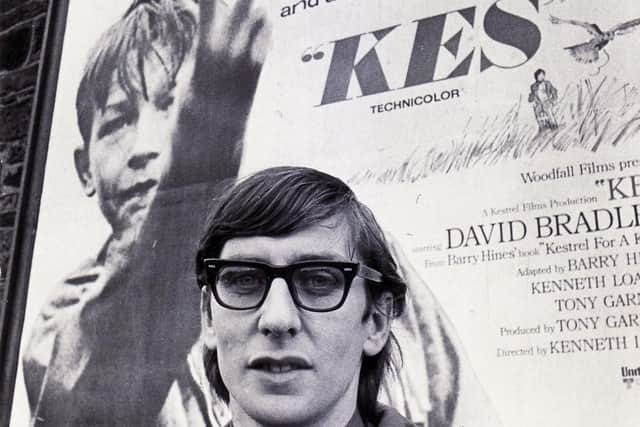

Half a century on from what is perhaps still his most defining screen moment, director Ken Loach speaks about the legacy of Kes, his classic Barnsley-based adaption of the Barry Hines novel A Kestrel for a Knave.

In an interview with The Yorkshire Post to coincide with the run-up to the milestone - the film was released in London in November 1969 and to wider UK audiences some months after - the activist reflects on his memories of shooting in the summer holidays of that year, his long friendship with the late writer and, ultimately, the political limitations of cinema.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe drama follows the story of Billy Casper, a working-class boy facing a tough school and home life whose world seems to expand after he strikes up a deep bond with a kestrel.

And though bleak in many ways, it was the Yorkshire humour that caught the imagination of Loach, who took "huge enjoyment" from Hines's writing.

"We would just hold our sides with laughter at the rhythm of the language," he says.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAlthough born in Nuneaton in the West Midlands, he added: "I had always enjoyed the comics of Yorkshire and Lancashire. The humour is my humour, really."

Loach recalls his first meeting with Hines before filming on location at what was then St Helen's School in 1968.

"We walked from his house in Hoyland Common through the woods to the wall in the book, which is where Billy found the kestrel. That was how it came about, really."

Through the expertise of cinematographer Chris Menges, the crew took influence from Czech films created in the the same decade - "small, but beautifully made," says Loach - amid the real-life drama of the Prague Spring.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a period famous for reformist Alexander Dub?ek's call for "socialism with a human face", until other Eastern Bloc forces suppressed the movement in what was then Czechoslovakia.

"In '68, Soviet tanks rolled into Prague. We were all deeply touched by that," said Loach.

"The cinematic influence was destroyed when we were trying to work in that tradition."

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd at 83-years-old, the recollections of shooting in South Yorkshire remain clear in his mind.

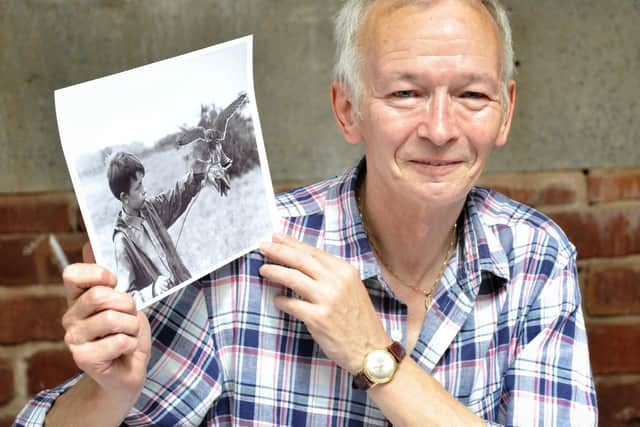

"The memories are still very vivid. Of Barry Hines, a great writer, and of David Bradley - we couldn't have found a better Billy Casper - a terrific lad then and a lovely man now still," he said.

"For the kids, they just didn't have a summer holiday because they just came up to the school every day because we were filming there."

The youngsters were particularly taken with the dinners made in a little caravan for those on set.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"They said the food was rather better than the food made in the school," chuckled the director.

He lets out a little laugh, too, remembering Brian Glover - a wrestler by the stage name of Leon Arras who played Billy Casper's comically domineering football teacher, Mr Sugden.

Both Loach and Hines went on to have prolific careers in their fields, and collaborated several times, but the novelist and playwright died in March 2016, aged 76, after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Paying tribute to his friend, Loach said: "He was desperately ill for many years at the end of his life. That was difficult, really, for him and everyone who knew him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I saw him a couple of times in the last few years, but he didn't know who I was.

"He slipped away. And it was tragic because he had a lot to offer.

"We could see it coming.

"We had talked about doing another film but this was before, I think, he was diagnosed.

"He was ceasing to be the Barry that we knew."

Their great moment won huge recognition, however, with Kes being ranked seventh in the British Film Institute's Top Ten British Films before the turn of the century - and is still thought of fondly by audiences in Yorkshire and beyond.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"It's always surprises me really, the warmth of people's enjoyment and sense of recognition, which is not limited to people in the north, really. The experience of those schools was across the whole country."

He added: "It's a huge recognition of Barry Hines's work and that's really satisfying.

"I owe them all a huge debt," he says, citing Menges and producer Tony Garnett.

The success of Kes was no minor feat for a small budget film which used the Yorkshire dialect - an uncommon decision at the time, and one that initially limited its reach.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen distributors United Artists organised a screening for American executives, one said he would have understood Hungarian better than the Barnsley accent.

"They were totally baffled by the film," says Loach.

Such social commentary also seems to have been lost on politicians in the UK.

Loach believes that without a wider movement, a film's ability to create change is restricted.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn made reference in Parliament to his 2016 film I, Daniel Blake - which won the Palme d'Or at that year's Cannes Film Festival - suggesting that then Prime Minster Theresa May take the time to watch it and heed its warnings about the UK's social security system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe filmmaker said: "It's gratifying, of course. It's recognition for everyone who's made the film. It's such a cliche but it belongs to everyone."

But ultimately, he adds: "It's had no effect whatsoever on the Government, which is now worse."

He balks slightly, also, at the suggestion that he gave a Yorkshire town its voice.

"Barnsley has its own voice, particularly through Barry's writing - I must stress that," he said.

"Full respect to that and the people there."