Only one Premier League team, no Ashes Test and rugby league crowds falling - how sport lost its Yorkshire heart and soul

GIVEN the success of Yorkshire’s sportsmen and women at the just finished Rio Olympics, it may seem an odd time to be arguing that the White Rose county has endured decades in the sporting doldrums. Throw in back to back County Championships for its cricketers and a decade of success which has seen Leeds Rhinos sweep all before them and Anthony Clavane’s case gets a whole lot flimsier.

But dig a bit deeper beneath the surface and it’s hard not to think the author might have a point. There is currently only one Yorkshire team in the Premier League; several of them have lurched from financial disaster to despair, tumbling down the divisions. The world famous Headingley is no longer an Ashes Test ground and attendances at rugby league matches are falling. Throw in tragedies such as the Bradford Fire and Hillsborough Disaster and suddenly things don’t look quite so rosy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“When you do a book like this there will always be exceptions and I’m not saying the whole of Yorkshire is the same,” Clavane insists of A Yorkshire Tragedy. “But the idea was to look at Yorkshire and ask the big question which is very relevant at the moment: Why does Yorkshire feel so left behind by the rest of the country, particularly London?

“My argument is that it was because of what happened in the 1980s that Yorkshire’s voice, not just in sport but in culture, politics, the arts and so on has been marginalised. That’s a tragedy for Yorkshire but for the country as well.”

The book is the final part of a trilogy in which Clavane has used the prism of sport to examine the region’s social history. Promised Land: A Northern Love Story linked Leeds United’s highs and lows to those of the ‘beautiful game’ itself and the parallel journey of the city. Does Your Rabbi Know You’re Here? charted the contribution of the Jewish community to English football.

Although ostensibly about sporting decline, a Yorkshire Tragedy examines the bigger issues at play alongside it: identity, belonging and a sense of community. And Clavane says it could just as easily have been titled A National Tragedy as many of the themes are common to areas around the country.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLooking at football, rugby league and cricket, he argues that the collapse of British industry and erosion of a sense of community sparked by the Thatcher years continues to have long-term ramifications.

“In the post-war period Yorkshire was the counterbalance to London,” says the Leeds-born writer. “Sheffield was the City of the Future, it had these fantastic housing estates going up, a great sense that it was the city of tomorrow. Even in places like Barnsley, you had one of the best films in the world, Kes, being made there and people like Michael Parkinson and Brian Glover coming from there.

“It just felt there were a lot of Yorkshire voices around that were nationally important. That these towns and cities could find themselves on the big stage. Even a very small town like Featherstone, can you imagine a town with 10,000 people in it winning the rugby league Challenge Cup?

“It would be impossible today but they won it in 1983 and that was the last time you had a town like that, which was based on the mines, achieve such success. It’s no coincidence that if you get rid of the mines you then get rid of the power and reduce the morale of a town which has been built around mining, steel, the mills or fishing.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“So this is a story about Yorkshire sport but it also charts the loss of that post-war sense of optimism and advance by Yorkshire as a counter to London. Today London is booming and although there are some places like Leeds doing well, on the whole there is a huge gap. When I grew up that gap was closing and at times it felt we really were God’s Own County.”

Few could contest Clavane’s assertion that football’s Premier League has become almost a Yorkshire-free zone, apart from Hull City who yo yo between the top league and the Championship. Meanwhile, the likes of Leeds United and the Sheffield clubs languish in the second tier.

“These are three of the most famous football clubs in the country and they’ve been struggling for a long time,” he says. “Why has a county of six million only got Hull, who go up and then come down again, in the top flight? Does it mean we’re a second tier county? No. And yet we know the Premier League is the only show in town, so it feels like our exclusion from it is symbolic of what’s gone wrong.

“If you then look at rugby league clubs like Featherstone and Hunslet who in the past felt they could have a good run, get in the top flight and go to Wembley, the gulf between the Super League elite and the rest is growing. I think rugby league as a sport is overlooked because it’s dismissed as a minority sport.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Rugby union is the Establishment sport and the coverage it gets is far greater and more importance is attached to it. That reflects the North South divide.”

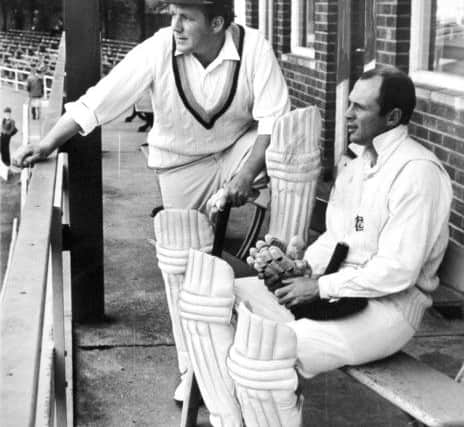

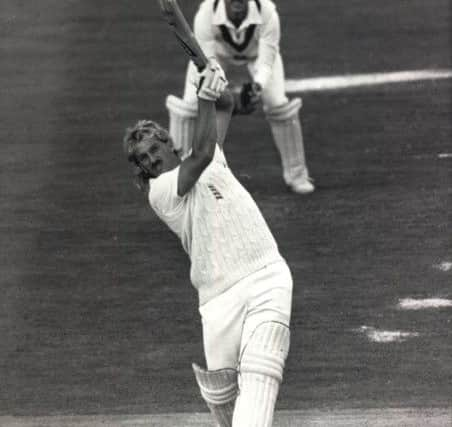

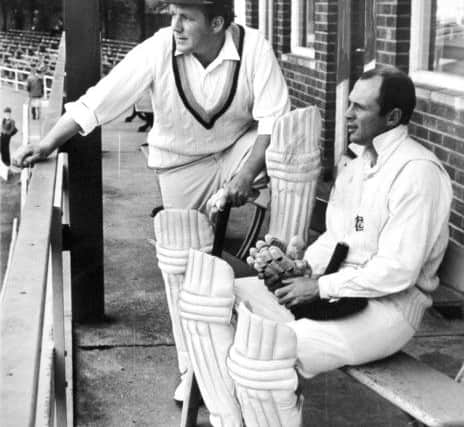

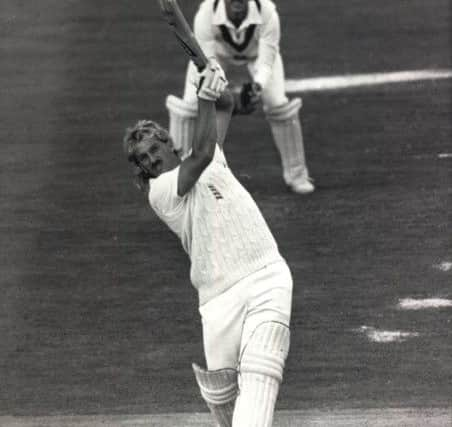

When Clavane started writing the book Yorkshire CCC had spent 30 years in the wilderness. He contends that the club tore itself apart in the 1980s and is only just starting to recover. “I’m very pleased to see its recent success, but I’d ask at what price? There is huge debt that Yorkshire has to pay off and Headingley is not the ground it was. I write about Botham’s Ashes in 1981, it was unthinkable that Yorkshire wouldn’t have an Ashes Test.

“It’s great that Joe Root and others are coming through but when I was younger I could go and watch my heroes like Boycott and Chris Old at Headingley or on TV. Which Yorkshire kids can do that now? Joe Root plays more for England than Yorkshire and when Yorkshire are on the telly it’s on Sky which still only a minority have.

“Where will the next generation of Joe Roots come from? The likes of Boycott, Close and Trueman were of the people and the people followed what they did. It’s the same in football, the working classes often can’t afford a ticket.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUltimately, his book asks the question of what happens when industries leave town, communities become fragmented and even collapse. When sport has been an outlet for these communities, their way of announcing themselves to the world, what happens when that starts to suffer?

For some British sport has lost its heart and soul. Clavane argues that it has lost its “Yorkshireness”, which he argues is essentially the same thing.

“Sometimes I’m just using Yorkshire as a shorthand for the people who have been left behind in Britain,” he says. “I haven’t got a chip on my shoulder, but I do feel the London and Westminster elite have shamefully neglected a great resource of talent, a great area of this country and that’s been happening for the last 30 years.”

A Yorkshire Tragedy is published by Riverrun on September 1, priced £16.99.