Why a century on Passchendaele remains a by word for the horrors of war.

CHARLES Harding Smith’s wife and parents never knew how he died. All they knew was that on October 9 1917, at a place called Wallemolen, in Flanders, he vanished aged 34, his life obliterated so completely that there were no remains.

The only things left of him were the few relics of officialdom, the standard letter of commiseration from George V with a memorial scroll, and a pro forma acknowledgement card showing that he had received a letter from his family on September 9 and a parcel the next day. That letter and parcel were probably Private Smith’s last contact with his wife, Mary, and his father, John, in Leeds.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was one of the thousands of Yorkshire troops who fought and died at the Third Battle of Ypres, which began 100 years ago on July 31. But history came to know the battle that became a byword for the worst horrors of the Great War by the name of a nondescript village being fought over – Passchendaele.

Even by the war’s bloody standards, this was a uniquely appalling episode, a drawn-out fight to the death in conditions so nightmarish that the soldiers who were there routinely described it as Hell on Earth.

Ferocious bombardments and torrential rain turned the battlefield into a massive quagmire of liquid mud in which men and horses drowned. They slithered along duckboards to the front line past fetid pools of water poisoned by mustard gas that belched and bubbled because of the decomposing dead below the surface.

The battle raged for 100 days, costing a quarter of a million Allied dead and wounded, and probably as many German, for the gain of just a few miles in pursuit of high ground from which to batter the enemy with artillery. And then, within months, the terrain that had cost so much blood to capture was surrendered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter all the loss and horror, the Allies pulled back in a tactical withdrawal to a position that commanders had advocated before the fighting even began. It had all been for nothing, a mass sacrifice of men for the most futile of objectives.

There will be official commemorations in Ypres of the start of the battle with members of the Royal Family and the Government in attendance, but in this part of Belgium, remembrance is ever-present. At its heart is Charles Harding Smith, roll number 48888 of the 8th Battalion, the West Yorkshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s Own).

The dry official record that he was dead sent to his widow forms a centrepiece of the permanent exhibition at Tyne Cot, the world’s largest Commonwealth war cemetery.Here too is the war roll card that he signed on August 24 1917, saying he was Anglican and that his parish church was St Aidan’s on Roundhay Road, Leeds. And in what must have been a bitter irony for her, here is the letter to his widow that accompanied his Victory Medal.

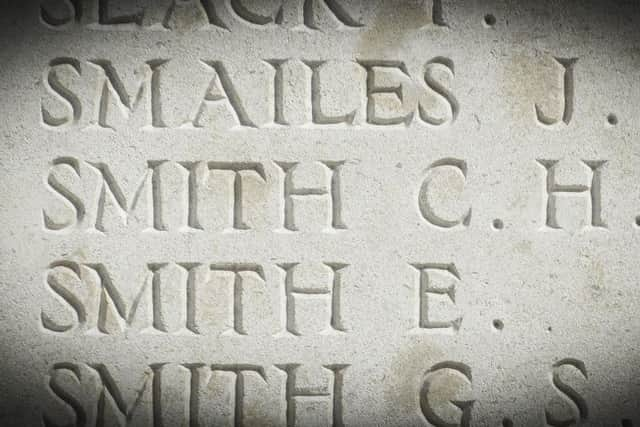

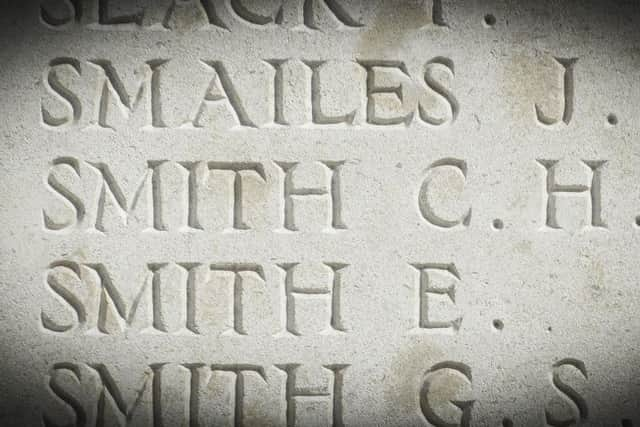

There was no victory, no armistice, no reunion with Mary at their home in Roseville Terrace for Private Smith. His memorial is his name, carved into the white Portland stone of panel 46 of the cemetery, just one among hundreds of his comrades from the West Yorkshires who were never found.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis is a quiet corner of remembrance to Yorkshire’s lost in that terrible battle. Alongside the West Yorkshires are the names of the East Yorkshire Regiment soldiers who were never found. Among those is Lt Col J H Coles DSO, and at the foot of the panel is a family wreath to his memory, inscribed: “In honour of Jim Coles, from some of his grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great grandchildren.”

It is a moving tribute, as is that below the panels commemorating the men of the Yorkshire Regiment, left by a party from Wickersley School and Sports College, in Rotherham, who have written: “Our generation has a duty to remember past conflicts and ensure that history does not repeat itself.”

The scale of the losses that the cemeteries and memorials represent is so vast that visitors visibly struggle to take it in. Besides Tyne Cot’s 12,000 graves – more than 8,000 of them of men never identified – the names of the Yorkshire troops are among 35,000 inscribed there who have no known grave. There is an even larger legion of the lost commemorated by the Menin Gate, in the centre of Ypres.

They marched to the front along the road where it stands, and 54,000 who were never found are recalled at 8pm every evening when crowds gather for a ceremony to sound Last Post. Ypres was flattened in the fighting, and the restored city is a memorial to what happened. The Cloth Hall is home to the high-tech, interactive In Flanders Fields Museum, which guides visitors through the story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA few miles away, in Zonnebeke, the more traditional Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 has recreated the dugouts in which troops sheltered and slept as best they could, which carry a sense of how claustrophobic it must have been. There is also a restored trench system that captures a flavour of what it must have been like to go over the top. But it is the less formal sites that are most eloquent of the cost of the battle. To walk through the flat farmland is to be reminded that beneath the fields are about 42,000 Allied troops whose remains were never recovered, and probably a similar number of Germans.

Passchendaele itself was obliterated. The rebuilt village – renamed Passendale – bears virtually no trace of what happened. Other sites, though, remain intensely evocative. One is the baldly-named Hill 60, just outside Ypres, where Yorkshire troops fought a ferocious engagement early in the battle. Markers showing where the front lines were speak of how desperate the fighting was, with the British and German trenches barely the length of a football pitch apart.

The only respite from the cruelty and horror of battle was to be found about eight miles behind the front line, in the little town of Poperinge. This was where the Rev Philip “Tubby” Clayton founded what became the Toc H movement in an elegant property, Talbot House, where troops could rest, eat, and find a few days’ peace.

As everywhere else in Flanders, remembrance of Passchendale remains central to the life of Poperinge. Even the church bells peal It’s a Long Way to Tipperary before the clock in the Market Square strikes the hour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was in memory of men like Charles Harding Smith and the unimaginable horrors that they endured that the Great War poet Siegfried Sassoon wrote one of his most powerful pieces, Memorial Tablet.

I died in hell - (They called it Passchendaele).

My wound was slight

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duckboards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

Andrew Vine and Mike Cowling visited Ypres courtesy of Visit Flanders, which has details of the full programme of commemorations of the Battle of Passchendaele. www.visitflanders.com