World Cancer Day 2021 Leeds: What it's like to watch your dad die of inoperable brain tumours - and how to carry on going

Yeah, that was my dad. Aged 69 years old, he led a conga train of mostly young girls during the song The Night Train in the middle of a crowd of 100,000 rock fans, just after the wine, just before the (declined) drug offer. I could only look on with a blend of horror, amazement and even a little jealousy.

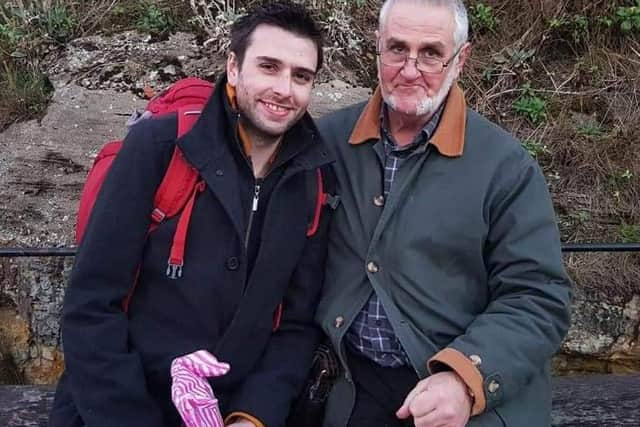

‘We’ll never have a better night than that!’, my dad panted to me as the three-hour drunken party finally came to an end and we trudged back to the Download Festival campsite on a father-son high. Four months later, he was in hospital with three inoperable brain tumours. Just like that, our festival days were over - and his days were numbered.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHow on earth do you cope with that? And how do you possibly even consider being able to come out the other side?

Today, on World Cancer Day 2021, I wanted to share a little bit about my experience of what I went through in the hope it might help others see that, no matter how bleak, you can come through this - or at least, keep on trying to.

It wasn’t something any of us saw coming. He’d been the life and soul that summer, but by October I was sat in a plastic chair in a poky hospital office as a clinician held up a scan image to show me: three unmistakeable clouds across the front of his brain. We can’t operate. How long? Maybe six months, they said.

From that point, life changed. It changed irreversibly. I was 29, so hardly a spring chicken, but that was the day that any final scraps of my childhood (read: manchild ways) ended for good. From that point, my dad stopped looking after me and for the year that followed, I looked after him.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe had been acting a little strangely for a week or so before the diagnosis. He was slightly insular when he came to visit. That was very unlike a man who was a vocal member of his local folk group - an activity I still suspect was a thinly veiled front for a group of older gentlemen to drink a different bar dry every week away from the glare of the folk WAGs.

He’d been off, not himself, and for the first few trips to the doctor we’d had every theory from stress to a water infection, to grief (his wife had died of Parkinson’s one year before), to general senility. It wasn’t until he tried to give his money away to random people in the waiting room that we feared something much more serious was brewing here, even if the words ‘inoperable tumour’ never for one second crossed my mind.

I never met my grandfather on my mother’s side. Apparently he died of a heart attack at 52, out of the clear blue sky when she was just 14 years old. Came home from school one day and he was just gone. Instead, I watched a brain tumour slowly claim my dad’s life. First it claimed his usually vibrant personality, then it claimed his behaviour and sometimes his dignity, and finally, one long and painful year after diagnosis, it finally claimed his life. I can say with all honesty that I don’t know which is worse, but I would not wish this experience on my worst enemy. Not even Leave voters.

The only thing that kept me going through that year was the idea of repayment. Moral, personal, familial - even cosmic or karmic - repayment.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEven as I whizzed off into the world, bounding with enthusiasm and keen to make my mark on the various cities I lived in as I pursued a career making money out of telling people about it's going to snow, my dad was my go-to guy. My phone-a-friend. Car broken down in the snow, on the M5, at 1am? Call dad. Washing machine leak pouring into my flat at 10pm? Call dad. Lonely and need a trip to the pub? Call dad.

Throughout my 20s, the relationship we had morphed from the ungrateful son who leaned on his father, to a true friendship. When I moved to Yorkshire in 2014, I had no idea it was to be for the final stretch of my dad’s life. But in that five years, we went to Download Festival together five times. We went to Barcelona for his stag do. We set the world to rights on politics, on religion, on human nature, over one too many beers. We stopped being father and son. We became friends.

So here I was, sat by his hospital bed, facing up to the certainty of my dad’s death. The only thing I could vow to do, the only thing I could think that could get me through it at all, was that this is my chance. My chance to repay my dad for everything he ever did for me. I would be there for him, whatever he needed.

At the start, that was just me bringing him Pepsi Max (clearly a genetic weakness in the family) and Wispa bars. By the end, I was practically force feeding him custard to keep his strength up. In-between, I am so immensely proud that I managed to check him out of the hospital for a few final trips: I got him to Whitby, I got him to Weston-super-Mare for one last trip to the seaside, I even managed to get him to one final, bittersweet, mostly bitter, trip to Download Festival.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAfter that, he became too ill to venture out again. For the following six months, my only goals were: keep him company, try to keep him alive for as long as he appears to want to. Towards the end, the nurses told me the only time he’d eaten anything was during the hours I sat by his bedside.

Mercifully, this was pre-Covid times. I cannot imagine I could have coped if I wasn’t able to do that because of this sodding virus. I can’t imagine how much worse so many families out there have it right now, in this very same situation in a pandemic and unable to sit by there bedside like I did.

Right to the very end, dad battled. He rallied. Even on the days he slept for 23 hours out of 24, he tried to eat. He tried to talk. He looked at me and I saw the spark of recognition in his eyes. It was only on that final day, that final evening, that I knew he was ready to go.

I put on our Download Festival playlist, took his hand, and he opened his eyes, sat up, looked straight at me, smiled, then laid back down. Paint It Black by the Rolling Stones blared over the speakers. He was gone. He was still holding my hand as he died right there in front of my eyes.

Coming out the other side

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdRecently, the feeling of broken-glass-in-the veins has begun to wane. It has felt like the colour has begun to return. I feel myself making more jokes. I want to write again. I want to read again. The world has become more interesting, the people in my life more interesting, and more inspiring. If you’ve been around me or speaking to me in the last few months: thank you. You’re one of the people that’s helped bring me back. Working on my dream job, as Head of Live News, working hard on breaking news every day, has helped bring me back.

And it’s now that I realise how much of that personality - now it appears to be returning - I owe to him. Whether it’s the stupid dancing, the crappy jokes, or the desire to drink one too many whiskies, I feel my dad’s presence, right there in my blood.

To anyone else going through a similar experience: the loss of a loved one, the loss of a friend not just with cancer but maybe with Covid: It’s a cliché, but it does get easier. Don't be afraid to get help. Go to the doctor. Get counselling. Don't bottle it up. Speak to people.

The biggest help I've found is to keep Ivor's memory alive through sharing memories of him - so thank you for keeping him alive by reading this far.

If you or someone you know is struggling with cancer, or wants to talk to someone, call the Macmillan Cancer Support line on 0808 808 00 00 or go to https://www.macmillan.org.uk/

Comment Guidelines

National World encourages reader discussion on our stories. User feedback, insights and back-and-forth exchanges add a rich layer of context to reporting. Please review our Community Guidelines before commenting.