The curious Yorkshire contraptions shining a new light on science

TUNING forks, an odd-looking camera and a Heath Robinson contraption that claims to be able to predict economic armageddon.

They hardly seem the ingredients of a good night out, but these objects are among those revealing the fascinating history of scientific development – and the part Yorkshire has played in it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdExperts at Leeds University are using them as the starting point for a series of public lectures which examine how they help us to understand what science is, what it has been in the past and also what it can tell us about the way we see ourselves and the world around us.

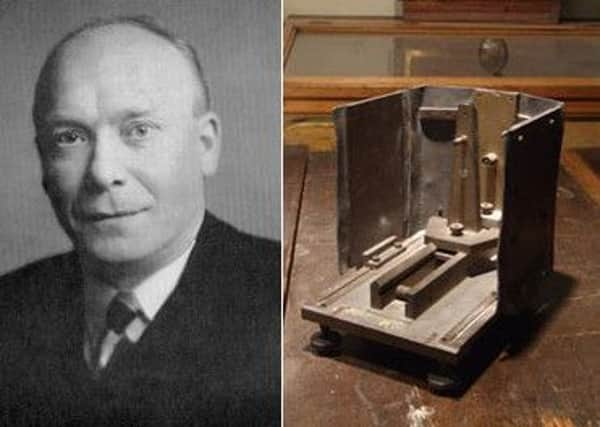

The Astbury Camera, for instance, captured the first ever X-ray images of DNA. It was the work of pioneering Leeds scientist William Astbury who made the first steps towards discovering the structure of the genetic material in the 1930s.

The discovery of the DNA double helix was made in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick. But they were dependent on the work of X-ray crystallographers, skilled in the taking and interpretation of patterns created when X-rays diffract though biological fibres in crystalline form.

“The most famous and best-known tests are linked with Oxbridge and London,” says Dr Mike Finn, director of the Museum of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at Leeds University. “But it was here in Leeds that the first X-ray of DNA was actually taken.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAstbury, who coined the phrase “molecular biology”, pioneered X-ray studies of this kind at the university throughout the 1930s, 40s and 50s – paving the way for the seismic discoveries that followed.

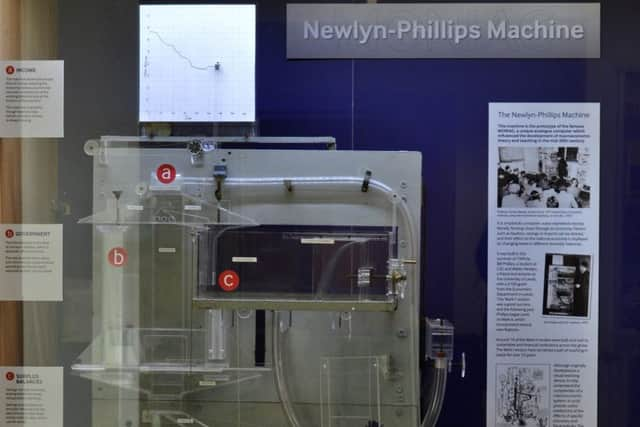

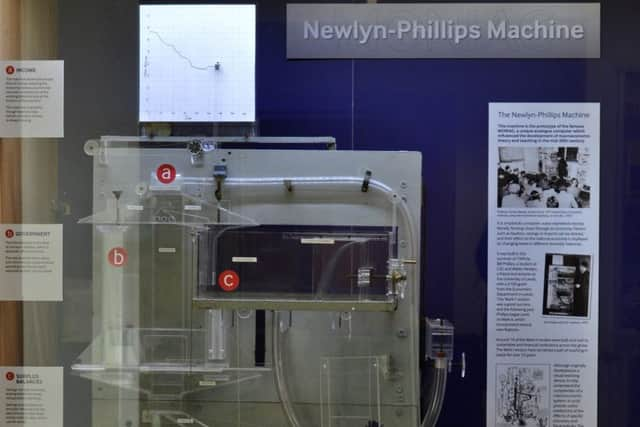

Then there is the Newlyn-Phillips Machine, a hydraulic computer which uses water to represent money, literally flowing down through an economy.

Also known as the MONIAC – Monetary National Income Analogue Computer – it was built in the summer of 1949 by New Zealander Bill Phillips and his friend Walter Newlyn, a lecturer at Leeds University, using a £100 grant from the economics department.

Factors such as taxation, savings or imports can be tweaked by altering the flow of water, showing what effect they would have on the national economy. “It was accurate to four per cent and was one of the first computers used in economic analysis,” notes Finn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Newlyn and Phillips made around a dozen models of it and travelled around the world. They ended up selling them to the likes of the Ford Motor Company, Harvard Business School and the Central Bank of Guatemala.”

These homegrown artefacts are now the stars of the show in the free lectures aiming to tell the history of science in 20 objects from the university’s scientific collections.

The next one will take its cue from tuning forks. “That’s right, tuning forks,” Finn confirms. “We’ll be talking about how important they are in science, the study of deafness and how the mathematics behind them started with Pythagoras 2,500 years ago. It’s telling an interesting story about what, on the face of it, is a pretty mundane item.” The lectures have been well received, with more than 100 people turning up to the last one. “Academic events don’t always do that great so to have that many people turning up was brilliant,” says Finn. “No specialist knowledge is needed to come along. They’re aimed at a people of all ages who would like to learn about the history of science.

“Hopefully people will keep coming and by the end of the series they will have a working knowledge of the subject.” The department is also working on a museum of the history of science, technology and medicine which it plans to open up to the public.

For more information visit tinyurl.com/z2edpw5.