Northern identity - putting the accent on art and design

“I became fascinated with this really vague, slippery concept of northernness that everyone knows what it is until you start asking questions and you realise it’s at least 30 years out of date,” says Oli Bentley, creator of These Northern Types, from his office at Leeds-based design agency Split.

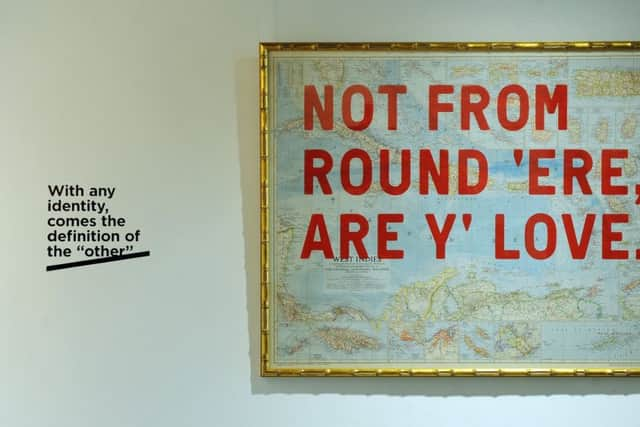

It’s a fascination that started a few years ago and ballooned, turning into a project that uses typography to poke round the gap left by our outdated ideas about northern identity. The project itself is almost as difficult to nail down as the subject it explores, but its main pillars are an exhibition of 16 artworks and a book with 16 corresponding essays, along with what Oli calls the ‘People Powered Press’, a printing press that may be the largest of its kind.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe exhibition is on display at Colours May Vary, an independent book shop and art space in Leeds, which coincides with an accompanying book.

It began with questions. “We’ve talked to a lot of people, because who the hell am I to tell people what northern identity is?” says Oli. Hundreds of conversations followed, and each of the artworks and essays grew out of a specific interview.

The works themselves range from the fun (including ink made out of chip shop curry and gravy) to the provocative (an attempt to trademark ‘The North’). Meanwhile the book is separated into a series of smaller pamphlets by writers including the likes of fell runner, playwright Boff Whalley; poet Anthony Dunn and Nude magazine founder Suzy Prince.

Typography runs through the heart of it all, partly because it affords the opportunity to incorporate language into the design, partly because it’s simply what Oli does as a designer. It couldn’t just be a digital exercise, though. Crafting a northern typeface, Oli felt he needed to create something that could have a physical life out in the north.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“We wanted to create a typeface that felt northern, and how do you do that? We took the cross-section of a steel I-beam and extrapolated out from it. But that was a bit abstract, and we realised no-one was going to associate it with the north unless we started doing things up here with it. We wanted to inject that association into it,” Oli says.

The end result is a press that’s “precision engineered within an inch of its life” by JKN Oiltools in Batley. It’s already been used for workshops and printing projects, and the intention is that the press will live on after These Northern Types, visiting galleries and industrial museums as well as getting used by various community groups.

While the north is the project’s focus, it’s also supposed to act as a stand-in for other places. “The idea is that we use northernness as a lens to look through to examine our relationship to place,” says Oli. “A lot of this stuff applies all over the UK. All the issues around a London-centric bias apply just as much in Devon as they do to us. There’s a north/south divide in Wales and there’s one in Italy.” It’s about living away from the centres of power, media and culture.

What emerges is in a lot of ways the opposite of a designer’s usual job, which is to reduce something down to easily identifiable iconography. As Oli writes in his introduction to the book, “Any notion of a clearly defined ‘essential’ identity that encompasses 14.9 million people doesn’t quite cut it.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe existing ‘essential’ northern identity is, Oli argues, backwards-looking. “A focus on our past is inevitable,” he writes. “It is easy to look back through history’s simplified, organised pages and see a clear picture of how things were. But the now is, and has always been, messy. The now is ill-defined, an ongoing battleground.”

So what we get is a ‘typical northerner’ who’s a white, working class male. The idea of a friendly, salt-of-the-earth, no-nonsense grafter might be comforting for some, but there’s a fine line between identity as a positive, unifying force and it serving to exclude anyone who doesn’t fit the mould.

Other writers have tried to add nuance to our ingrained ideas about northern and English masculinity. It certainly hasn’t hurt that These Northern Types has launched the summer that chants of ‘It’s coming home’ swept across the country. The St George’s cross has become a topic of debate, with some linking it to racism.

“I think the reason [for that] is it’s been co-opted by the far right,” Oli says. For the people who feel uncomfortable about the English flag, “The one time they feel positive about it is around the football, the cricket, the rugby.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile neither the book nor the exhibition offers a tidy redefinition of northernness, one thing that does crop up repeatedly is geography and landscape. “Physicality is definitely an important feature of the writing we’ve received for These Northern Types,” says Anthony Dunn, who helped edit the book as well as contributing to it.

“Many of the authors have talked about the strenuous nature of walking or cycling in northern landscapes, of hard labour in northern mines, or the clashes on our northern football fields. And yes, we definitely seem to be proud of our landscapes. People have such love for Malham Tarn and the Lake District and the bridges across the river Tyne and - you know - the list goes on and on.

“But I don’t know that we’re more closely tied to our landscape than people who live on the Norfolk coast or on Dartmoor. I do think that where the labours that have defined communities are intrinsically linked to their landscapes - like mining or fishing, for example. And the north of England does seem to have been blessed with more than its fair share of extraordinary landscapes, doesn’t it?”

“The geographical difference is so stark and obvious. It feeds into people’s characters,” says Boff. “When Oli approached me about this, I went back to that story about being a schoolboy and thinking you can walk from the place where you live in the middle of a town and end up on top of a hill looking down on it, and I think that’s an experience that a lot of people in the north have. That feeling of, ‘I can escape and find something of myself’.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile These Northern Types might not serve up anything concrete to replace the outdated cliches of northern identity, it does treat that empty space as an opportunity to claim control of northernness for actual northerners.

“Ironically, a lot of what’s said about northern identity is controlled from the outside,” Oli says. But as writer Phil Kirby, quoted in the book’s introduction, puts it: “Northern identity is a myth. It’s always been a myth. But we live by myths, which is why I think we ought to be careful with our northern story... we northerners have a responsibility to make it a good, progressive, positive myth.”

The Northern Types exhibition continues at Colours May Vary, Duke Street, Leeds, until September 15.