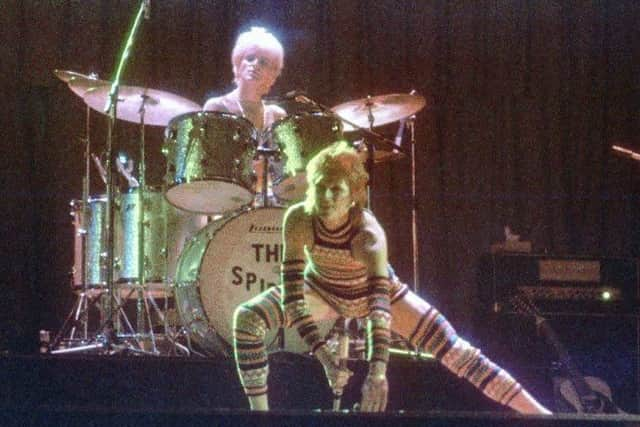

Music interview '“ Woody Woodmansey: '˜Ziggy Stardust took a hold so strong'

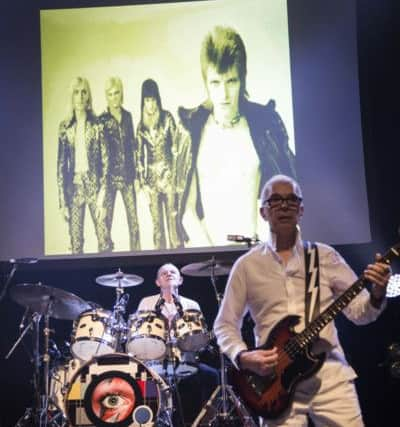

The last time Holy Holy, the supergroup formed by Woody Woodmansey and Tony Visconti to perform the songs of David Bowie, embarked on a full UK tour they presented his third album, The Man Who Sold The World, in its entirety.

In their 2019 schedule they’re adding one of the singer’s most-loved albums, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars, to their set.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor Woodmansey, who is the last surviving member of Bowie’s early 1970s band the Spiders from Mars, it’s going to be an intriguing experience. “We haven’t tried it yet,” he says laughing, “but I’m sure it will work – and then pull a few from Hunky Dory and Aladdin Sane in between – so I think we’re playing for about a week!”

The Driffield-born drummer, now 67 years old, remembers “a really creative time” making Ziggy Stardust with producer Ken Scott at Trident Studios in Soho in 1971. “We’d done The Man Who Sold The World which was everything plus the kitchen sink on that album, then we pulled it all back for Hunky Dory, which, for me anyway, was David’s songwriter album, saying ‘Give me and elastic band and I can stretch it and write you a hit song’.

“Everything he seemed to write at the time was a great song and we’d streamlined our playing, I think we’d grown a bit as musicians, so Ziggy was like going back halfway between those albums. We needed the raw power of a rock thing but with a futuristic, streamlined edge on it. That was kind of the concept.”

Bowie himself was wearying of the dressed-down authenticity of much of the music of the period, suggesting that “rock should be tarted up and made a parody of itself”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWoodmansey recalls there being many discussions between the band, who also included Yorkshire-born guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist Trevor Bolder, about the need to “kick the music business up its a*** and brighten it up, it needs a bit of life and controversy and rebellion”.

“It was a nail-biting period because you were kind of going out on a limb, the way you looked and what you were playing, and it didn’t always go down well in certain places. Certain people were not ready for that, so it was edgy.”

Getting into Trident Studios was, he says, “a bit of sanity, really, we’re just doing music now”. With Ken Scott “getting really good sounds from us for the instruments” to bolster songs as strong as Five Years, Ziggy Stardust and Suffragette City, it seemed little could go wrong.

Woodmansey remembers the sessions had their light-hearted side too. He recalls complaining to Scott that on Hunky Dory the producer made his tom-toms “sound like I’m hitting Yorkshire puddings and I’ve got a crisp bag for a snare drum”, and asking “Can you make it better than that?” When they returned from lunch, Woodmansey found his drum kit had been replaced by “a crisp bag, a Kellogg’s Cornflake packet and some coffee cups and they’d all been mic-ed up with proper microphones, it was set up like a little drum kit and there was a pair of sticks there”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I lost it and everybody else behind burst out laughing. It was a good time; there were fun times as well.”

When they were recording the apocalyptic Five Years Bowie suggested that Woodmansey should open the song with a drum pattern. “He said, ‘It’s about the end of the world’ and I was like, ‘Oh yeah, put it on my shoulders. I’ll come up with something that sets it up for that’. I remember thinking ‘it’s a chance for me to be a bit flashy’ and then as I got into it I thought ‘Nah, it’s the end of the world, you’re going to be in despair and it’s all hopeless’. So I just had to get into that mood and see what came out. I just started playing and he went, ‘I love that’.

“Then when he was putting the vocal on that track, at the end of it the lights were really low in the studio, there was just a dim light where he was singing and he was crying his eyes out at the end of it. We were like, ‘Oh my God, you’ve got David Bowie crying coming through a 1,000-watt amplifier’. It was pretty emotional.”

Having witnessed Bowie’s own confusion as he tried to figure out how he could incorporate his many interests, including acting, musicals and mime, into his performance, Woodmansey found it fascinating following him on his voyage. “To be honest when we joined we were a rock ’n’ roll band,” he says. “We didn’t really look at music as being part of the culture; it wasn’t part of our vocabulary. He took us I guess on an educational trip, so that we could understand where he was coming from, what he wanted to do, how he saw it.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I remember one night he said, ‘I’m going to see a play tonight’ I said, ‘What’s it called?’ He said, ‘I don’t give a s*** what it’s called’. I said, ‘Why are we going to watch it then?’ And he said, ‘Because the lighting director is the best one in London at the moment. I want you to watch what the lights do and how he changes the mood in the theatre’. Then we ended up going to a ballet one night to watch the choreography and the balance on stage, just to get a more theatrical viewpoint of things.”

For three working-class Yorkshiremen, the prospect of wearing make-up was initially unwelcome. “I think it was when Starman came out and we were doing Lift-off with Ayshea, that was the first TV show we did, and we were brushing our hair and getting as good-looking and sexy as we could at the time, and he took this bag out and it was full of powder puffs and brushes and mascara and he stopped us in our tracks.

“He kept putting panstick on his nose and his face and he didn’t bat an eyelid. He said, ‘Why are you not putting make-up on?’ He got three Yorkshiremen answering him in a manner I couldn’t repeat. Again he didn’t bat an eyelid, he just said, ‘That’s a shame.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And he said ‘You haven’t played under these bright lights in studios before. What it has a tendency to do is suck all the life out of your face, your face will look a bit like an egg and possibly a little pale green so you might look a bit ill and it’s a shame because I’m sure you’ve got a lot of friends watching’. He didn’t have to say anything else. The next words were ‘So what do you do with this?’ And then he gave us a quick demonstration of how to put make-up on.

“He said himself later about when we found out what effect that had on the girls, then you’d hear things in the dressing room like ‘Who’s nicked my mascara?’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn its release in 1972, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust reached number one and Bowie and the Spiders embarked on a year-long world tour. In the States cracks began to appear in the previously close-knit group as Bowie began to immerse himself in the dissolute persona he had created. “It did get strange,” says Woodmansey. “Whereas before it had been you came off stage four guys that had just been up there playing and jumped in a limousine and had a good laugh and joke about partying or hitting the clubs. Then you found that Ziggy was in the taxi with you. It was always a creative thing that he’d put on and took off when he came offstage. Now you’d were talking to Ziggy Stardust. You can’t say, ‘Did you watch the football last night?’ There was a different relationship developing.

“He would come to soundchecks, sing a bit of a song then turn around and go whereas before we’d do proper soundchecks and it was all part of preparing for the show. Then they’d say, ‘David’s not staying at this hotel, he’s at this other hotel’, whereas before we’d book the floor of a hotel, all the rooms were left open, basically, because there were 45 of us on the road, so it was like your own little city. So that got different. We accepted that, we thought he is the star, that’s what all the press says, but it made it a little weird.”

At the Hammersmith Odeon in 1973 Bowie announced that the band was breaking up. It came as a shock to Woodmansey and Bolder but as the years have passed, Woodmansey can see it made sense in light of what the singer would go on to do. “We had talked during that last English tour about some of the ideas he had for more different music and things like that. He said, ‘I want the musicians not to be featured onstage, to be dressed all in black and stand in the shadows’. By that point we all had mouths and we understood the game, so it would be like ‘Sod off, I’m not standing in the shadows. You helped bring me out of the shadows’.

“And saying he was going to do soul stuff, which was not really our cup of tea, not that we probably couldn’t have learnt it but it wasn’t our natural musical genre. We’d all played everything but you end up having an affinity and ours was rock ’n’ roll and that was really what we excelled at.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Looking back on it, as I was able to do, I think it was a matter of life and death. I think if he hadn’t killed Ziggy off it would have killed him off. It took a hold so strong, it was like an actor playing a psycho who has to be that day in, day out on set and then can’t take it off. It wasn’t sane.

“I watched some of the interviews from that time and the non-sequiteur answers came across as just part of Bowie weirdness but it wasn’t, it was like he was a bit lost in it. He was trying to find ‘how does Ziggy answer this?’ because that’s what they wanted and he was having trouble with it. If he couldn’t deal with us as Ziggy then he couldn’t deal with anybody else.

“And he did get bored very quickly. When we were doing a song in the studio we had an understanding unsaid that you weren’t going to go four times through that song because if you did the session would go black, it would go very dark, he’d be bored and you wouldn’t get a good version after that. You had to get it in one, two or three takes because he got bored, he lost interest in that thing he was doing.”

In his memoir, Spider From Mars, Woodmansey mentions Bowie attempted to recovene the band in 1978 but Ronson declined to be to involved. It remains one of rock’s great what-might-have-been stories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I remember talking to Trevor [Bolder] about it at the time,” says Woodmansey. “We said ‘yes, we’d be up for that as long as it’s a pleasant environment’. I think he must have asked Mick on a bad day, basically, because he just said ‘No, I’m right in the middle of producing and I don’t want to go backwards’, so I don’t think he gave it much thought.

“I think, from my viewpoint, that David probably did better when he had a band that did understand what he was doing and were all on the same page totally, and I think he tried to do that again with Tin Machine, just to get that group spirit. By then it was too much solo David Bowie, you can’t drop somebody like that into an unknown line-up, so it was doomed to failure. But I think he was trying to get that back.”

He adds: “[At the end of the Spiders] we said things that we shouldn’t have said to each other and didn’t say a lot of things that we should have said, but we managed to do that when I met [David] in France in ’79. He said, ‘I’ve come to realise that the Spiders period was my rocket ride, that was my ride from the launchpad right to the top and I appreciate what you guys did for me and I’m never going to get that again like that’.

“It was interesting because he never said that to us when we were with him,” Woodmansey chuckles ruefully. “I guess he had a high expectancy anyway, he just expected you’d do your job and you would pull it off and he didn’t have to worry about it.”

Holy Holy perform at York Barbican on February 8, 2019 and then tour. www.holyholy.co.uk